Courtesy of My Generation.

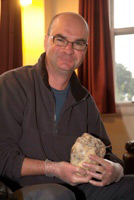

Stuart Watson keeps his heart in a plastic bag on his dressing table. Whenever he gets it out and looks at it, the Tauranga father of two, who was born with a congenital heart disease, can’t help wondering, “How the hell did that keep me alive for 42 years?”

Stuart Watson keeps his heart in a plastic bag on his dressing table. Whenever he gets it out and looks at it, the Tauranga father of two, who was born with a congenital heart disease, can’t help wondering, “How the hell did that keep me alive for 42 years?”

A healthy heart is about as big as your fist, but Stuart’s is nearly twice the size it should be, and covered in mottled fat. The heart keeping Stuart alive now used to beat in the body of a teenage girl. It was transplanted into Stuart’s chest on March 21 this year, and not a day goes by when he doesn’t think about its former owner and her family, who gave permission for her organs to be donated after she died of a brain injury.

“I’m desperate to write to her family to say thank you, but I haven’t done it yet because I don’t know how to put the words down on paper,” says Stuart, who knows nothing about the donor other than her age and sex. “How do you express your gratitude to the family for making such an enormous decision? I can’t imagine what they have gone through, losing their loved one. How do I find the right words to tell them what a difference this has made to my life?”

Stuart is one of dozens of patients who have received the gift of health thanks to organs from 25 donors in the first half of this year. That figure looks set to top last year’s total of 31 but our rates are still low and have dropped in the last 10 years. While you can officially record your wish to be an organ donor on your driving licence, if you do have a non-survivable brain injury and your organs can be used, it is your family who has the final say.

“I think there should be a registry, so it can be your decision, not something that is put on your family at what is a horribly traumatic time,” says Stuart. “That way we would hopefully have more organs available for donation.”

And that can only be a good thing, he says. Before his heart transplant, Stuart was living on borrowed time. Born with the two main arteries in his heart around the wrong way, he had open heart surgery when he was just eight days old, and another major operation just before his third birthday that meant his right ventricle did the job of the left, and vice versa.

While this kept him alive, it meant that his heart had to work extra hard and he quickly became fatigued. As a child he couldn’t do much physical activity – he was particularly devastated that he could never play rugby.

“The hard thing about having a heart condition is that you don’t look any different and people don’t realise you have this debilitating condition. I spent the best years of my life watching everything from the sidelines.”

His confidence was boosted in his teens when he discovered a talent for cricket, which required less stamina, but he just had to accept that there were many things he would never be able to do. “I tried to do as much as I could and I just accepted my boundaries.”

Stuart got a job with a company that maintains fire extinguishers but eventually had to give up work when he became too ill. He and wife Carole have two daughters, Danielle and Harriette, and he’s always tried to do ‘normal’ family activities like taking his daughters to their soccer games . But over the years his heart became so worn out it would take 10 minutes to walk the few hundred metres to the side of the soccer pitch and he’d have to sit down for the whole game.

His heart became enlarged from having to work so hard and he began suffering extreme palpitations. By 2007 he’d become so unwell he was told his heart was running at just 10 percent of normal function.

“Seventy percent is normal, 40 percent is very sick. When I was told it was 10 percent I knew I was in trouble.”

A heart transplant was really his only option, and Stuart went on the waiting list. After 18 months he got the call that would change his life.

“When you are told ‘this is it’ there are a gazillion things running through your mind. The biggest thing for me was knowing that to have this chance, someone had lost their life and their family had lost a loved one. It is a hard thing to get your head around.”

He has accepted the fact that another person’s heart has given him a second shot at life. Although it has only been a few months since the transplant he is already noticing big differences.

“I have so much more energy – now I can stand on the sidelines for my daughter’s soccer match. I can do the gardening and hopefully I will be able to return to work soon. Before the transplant my doctor said once you have your new heart your life will be transformed beyond your wildest dreams, and he was right.”

Stuart’s set himself a goal of one day cycling 160km around Lake Taupo – something he could have never attempted before the transplant – in aid of Heart Children New Zealand. He does a lot of work for the charity, including giving talks at which he shows his old heart.

“When they said I could have it I wasn’t too sure how I would cope with seeing it but I still feel that it is a part of me. But if I had had to keep relying on it I probably wouldn’t have been around for too much longer.”

While Stuart thinks of his donor daily, Tauranga couple Wendy and Paul Selby every day remember the six people who received their son Jared’s organs, donated when he was left brain dead after being hit by a car. They know that his heart, liver, kidneys and corneas went to five men and one woman and have had letters from three of the recipients.

Personal information like names can’t be given in correspondence between recipients and donor families but the Selbys have learned some details from the letters they’ve had. “The heart recipient had been very fit, ex-army, and he was able to go back to work after the transplant,” says Wendy. “He said, ‘I can’t thank you enough – you’ve given life back to a father and grandfather.’

“We asked to know how the recipients were getting on and the organ donor co-ordinator told us, ‘Jared’s heart just walked to the top of One Tree Hill this morning’. It’s difficult to explain how hearing that makes you feel. You are so glad that other people have been helped, but you have still lost your son.”

Adds Jared’s sister Melanie: “His death wasn’t a complete waste – it has saved six lives.”

Jared (22) was walking along a footpath in Hamilton with his girlfriend Johanna O’Connor on an August afternoon six years ago when they were hit by a car. The driver ran off the road into the couple while attempting to open a soft drink bottle. Johanna survived with terrible injuries but Jared’s head went through the windscreen and he was pronounced brain dead at hospital.

Paul and Wendy had never discussed organ donation with their soldier son, but after they were told he could not recover from his injuries they learned from medical staff that he had recorded his wishes to be an organ donor on his licence.

“They approached us about donating his organs and although we’d never talked about it with him we said yes because it was on his licence and that’s what he would have wanted,” says Paul. “And there was no point in burying him with perfectly good organs when they could save lives.

“It was quite an involved process – there was lots of paperwork to do – but we never felt like we were rushed.”

In fact it was two days before Jared’s ventilator was turned off – the Selbys waited until daughter Melanie could fly over from Scotland where she was living at the time.

“The staff were very supportive,” recalls Wendy. “It was an incredibly difficult time and they were there for us every step of the way.”

She says she has mixed feelings about knowing more about the recipients of Jared’s organs. “I used to think I would be interested in finding out about them and maybe even meeting them but now I am not so sure. Maybe it would be better just not to be involved.”

Paul is more sure of how he feels. “I wouldn’t want to meet them. Seeing someone who has his organs would just be too hard for me.”

Pete McInnes understands how traumatic it must for the families of organ donors but tries not to dwell on it. The real estate agent from Mangawhai needs a kidney transplant and says it’s hard to come to terms with the fact that his best chance of regaining his health will be if someone else dies.

“You just can’t think about it too much,” says Pete (52). “Of course you don’t wish for people to die but you think that if people are brain dead and on a ventilator, please let them be organ donors. Please let their families say yes to donating their organs.”

Pete, a keen surf lifesaver and triathlete, had always been healthy until a surfing trip to Bali six years ago. He picked up a bacteria which attacked his spine and nearly killed him. He spent a month in an induced coma, then came around only to get pneumonia and be comatose for another three weeks. He was in hospital for a total of four months, including 85 days in intensive care, and doctors told him he was lucky to have survived.

Unfortunately, the bacteria combined with the multitude of drugs Pete was given damaged his kidneys. They have gradually deteriorated and this year he had to start dialysis three days a week. He is still managing to work in between his treatments but is always tired. He’s had to give up surf lifesaving, socialising is difficult and he knows he’s likely to steadily go downhill unless he gets a new kidney.

His brother and sister have offered their kidneys but his sister doesn’t weigh enough and his brother’s blood pressure is too high. Two other friends are keen to donate theirs but aren’t compatible. So a kidney from a deceased donor is his best chance.

“Now it is just a matter of waiting and hoping,” says Pete, a dad of three. Like heart transplant recipient Stuart Watson, he’d like to see a drive to get people to tell their loved ones they’d like to donate their organs should they ever end up in a situation where they could help others.

“It’s the sort of thing that nobody likes to talk about but it is so important. I just wish people could make it known to their families that they want to donate because it could make the world of difference to people like me.”

Thousands of people every year agree to the word donor appearing on their driving licences, but very few of them die in circumstances that mean their organs can be given to sick people. And of those who do, it’s ultimately up to their families to give permission. Even if their licence says they want to be a donor, their family can over-rule that.

“It is very important to have a family discussion about it and make your feelings known,” says Janice Langlands, a donor co-ordinator with Organ Donation New Zealand.

She says a registry of donors would be expensive to set up and maintain and at the end of the day, letting your family know your wishes is still the best way to make sure your organs could be used.

Age isn’t necessarily a barrier to donating organs. People of all ages can be considered for liver and kidney donation, eyes can be donated up to the age of 85 and you can give your heart and lungs up until 65. Having a medical condition doesn’t necessarily preclude you from donating organs, unless that condition has damaged your organs i.e. you’ve had a heart condition. Corneas can usually still be transplanted even if you wear glasses or contact lenses.

See www.donor.co.nz.

Join the Discussion

Type out your comment here:

You must be logged in to post a comment.