Art in hospitals has a rich history, evolving from mediaeval religious themes to 18th- and 19th-century philanthropic efforts. Over time, with the advances made in medical care, hospitals became places where patients actually recovered so the art needed to keep pace. Back in 1989, the UK director of Arts for Health, Peter Senior, stated “art can benefit everyone and can play a part in maintaining and improving the health of the mind and body”. We now understand the transformative power of art and it is well recognised for its therapeutic benefits, including stress reduction and improved well-being for patients, visitors, and healthcare providers.

With all this in mind, a new discipline has appeared within the medical armamentarium. The “art therapist” has become a valued member of the medical therapeutic team using visual and tactile media as a means of self-expression and communication in order to help the individual to discover an outlet for what might be perceived as rather complex and/or confusing feelings. With art therapy, it is hoped the patient will become more self-aware and psychologically robust.

In the UK, art therapy is state regulated. In New Zealand, qualifications on offer include a Masters in Creative Arts (Clinical) and a Postgraduate Diploma in Creative Art Therapy. From a clinical perspective, I am reminded of a case where a teenage girl presented mute. The art therapist managed to get her to draw. One scene showed two young people fighting. As it turned out, one represented her brother who had raped her and then beat her up to “keep her mouth shut” – a powerful demonstration of the transformative nature of art.

A career in medicine can be a jealous mistress and demand one’s full-time attention. Therefore, most doctors become aware of the need to strike a balance between their professional and private lives – enter the arts. One day in 1989, I happened to be reading in the medical library when I came across an advertisement for the International Association of Artist Doctors, with headquarters in Barcelona. Thinking they may be a group of medical illustrators, I decided to drop them a line. Although the reply was written in Spanish, one line stood out: “Te membamos presidente de la union neozelandia de medicos artistas.” (We love you, president of the New Zealand Union of Medical Artists.) Clearly, I had been appointed president of the New Zealand Association of Artist Doctors.

After the mirth settled, I gathered some like-minded colleagues and drew up a constitution. Our first concert was held in 1990 and since then (except for Covid and earthquakes), we have held an annual art and craft display and variety concert. We now have a fifty-piece orchestra and a twenty-person choir, as well as solo performers and small groups. Participants come from all disciplines of medicine including general practice, specialities and from the student population. The most important component of the association is the fellowship. In this age of shared care, communication between health professionals is vital for the patients whom we all serve. Perhaps the transformative power of art is the reason our association has continued to flourish.

When I left school from the Upper Sixth form, I decided upon a career in medicine. Like all males aged twenty at that time, I registered with the Department of Labour for compulsory military training (CMT), determined by birthday ballot. Unfortunately, I won the ballot but as I had just gained entry into the University of Otago Medical School, I was assigned to the Otago University Medical Company (OUMC). At the conclusion of my fourth year of medical training, I was offered the opportunity of serving with the Combined Services Medical Team in South Vietnam for a four-month tour of duty. I saw this as an opportunity to take part in a humanitarian aid programme with the possibility of pursuing my passion for art in my spare time. So, armed with my stethoscope, a box of hard pastels, a can of fixative spray, pastel paper, biro pens and a sketch pad all squeezed into my army kit bag, off I went to war.

My time in South Vietnam was spent between three places: Quy Nhon, Bong Son (both located mid country and coastal) and Vũng Tàu (close to the Mekong Delta). During the day, I was assigned to either surgical or medical services and was required to perform minor surgery under supervision. At night I would return to the wards to paint portraits of patients I had met during the day. In addition, I chose civilians with whom we came in contact either in the course of our work or after hours. If I saw an interesting subject during my travels to provide civilian aid, I would ask my driver to stop so I could do quick sketches.

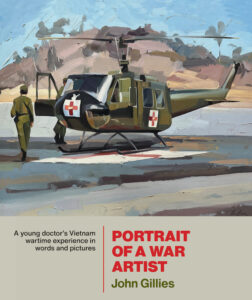

Through my art, I made friends and met people, both civilian and military, in the most extraordinary of circumstances. When I returned to New Zealand, I collected my letters home and notes made during my tour of duty with the intention of publishing a book through A.H. & A.W. Reed. Unfortunately, anti-Vietnam War feelings were at their height and the publishers were reluctant to proceed. Therefore, my manuscript, art works and photographs remained in the attic until very recently and my book, Portrait of a War Artist: A young doctor’s Vietnam wartime experience in words and pictures, has now been published through Quentin Wilson Publishing. Among other things, I hope this book will leave readers in no doubt of the transformative power of art.

Portrait of a War Artist by John Gillies, Quentin Wilson Publishing, RRP $34.99

Portrait of a War Artist by John Gillies, Quentin Wilson Publishing, RRP $34.99

Join the Discussion

Type out your comment here:

You must be logged in to post a comment.