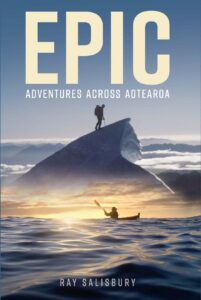

Extracted from Epic: Adventures across Aotearoa by Ray Salisbury, published by Exisle. Hardback RRP: $49.99.

Extracted from Epic: Adventures across Aotearoa by Ray Salisbury, published by Exisle. Hardback RRP: $49.99.

In 2013, Brando Yelavich dreamed up a naive plan to walk around the periphery of Aotearoa. Alone, on foot. The nineteen-year-old dropout jumped into the deep end and learned lifelong lessons on the move, living off the land for nearly two years as he negotiated 8000 km of coastline. This is the heartfelt story of a boy becoming a man.

Born into a middle-class family, Brando Yelavich was raised in the Auckland suburb of Greenhithe. From age six he trained as a gymnast, eventually practising five times a week and representing his region. At the tender age of twelve he went to the nationals where he topped his age group.

However, he was never going to comply with the conformity-based, cookie-cutter expectations of society — this kid was hard-wired for adventure. The restless youth was diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), which meant he couldn’t concentrate in the classroom. On top of this, he was diagnosed with dyslexia, so the odds were stacked against him. When he hit puberty, he was bullied at school, gave up gymnastics and became obsessed with computer games.

In his mid-teens, Brando’s relationship with his parents started to disintegrate so he was sent to Cromwell College, a life-changing opportunity. At this school in Central Otago, the Year 12 students combined their academic studies with outdoor pursuits. Here, the Aucklander was living in a student flat while being exposed to kayaking, abseiling, tramping and hunting.

About this time, he devoured the best-selling cult classic Into the Wild, a book by Jon Krakauer about Christopher McCandless who disappeared into the wilds of Alaska to ‘live off the land’. The body of McCandless, a college dropout, was eventually discovered inside an abandoned bus on the Stampede Trail — he’d died of starvation or from eating poisonous berries.

Inspired by this book, Brando had a brainwave. He, too, would do something dramatic: he would walk around the coast of New Zealand! This plan was outrageously foolhardy, but the idea sporadically burst into life like a novelty birthday candle that would reignite after being blown out.

Fast forward to 2012. Brando had returned to Auckland and could not hold down a job; he was also smoking marijuana joints every day. Despite some deep emotional issues, the youth genuinely wanted to turn his life around. Work and Income New Zealand sent him on a short course, along with other unemployed ‘misfits’, run by the Defence Force at the air base in Hobsonville. He was subjected to regular fitness drills, 10-km runs, rock climbing and tramping — right up his alley. In fact, Brando proved to be the best in his 30-strong platoon. By the end of this training, his self-confidence was at an all-time high, so he applied to train with the army.

Brando was rejected because of his dyslexia and ADHD. He was gutted but had an alternative scheme in mind to get out of the drug scene. He told his friends he would ‘walk around New Zealand’ in the new year, though no one really took him seriously. Despite the setbacks, despite the lack of emotional support from family or friends, despite the fact he was stone broke, the nineteen-year-old forged ahead with his planning. Determined to change his lifestyle, he believed that ‘there’s no such thing as being lucky. You have to make your own luck in this world.’

In the naivety of youth, Brando estimated the coastline of Aotearoa would take six months to navigate. He began manically training at a local gym, running, swimming and long-distance walking. As he began to seek sponsorship, his persistence paid off when a couple of businesses, including Stirling Sports and Kathmandu, agreed to donate gear. Later, Scarpa supplied a range of footwear.

To help him ‘live off the land’, Brando carried an assortment of gear including a collapsible fishing rod, a crossbow and air rifle. For protein he would hunt goats, rabbits and possums, then try his luck at fishing. Harvesting mushrooms, seaweed and ferns would add flavour to his diet. Not wanting to repeat the mistakes of Christopher McCandless, he bought a copy of Andrew Crowe’s A Field Guide to the Native Edible Plants of New Zealand. Along with the usual sleeping bag, tent and stove, a harmonica, rope and machete completed a growing pile of equipment. Small wonder his backpack weighed 60 kg at the outset!

Brando’s inexperience was mitigated by the inclusion of a personal locator beacon, and a satellite tracker so his parents could follow their son’s journey online and ensure he was safe. Using a GoPro camera, he would film video clips for his Facebook page and use the Google Maps app on his iPhone for navigation. (He soon discovered this did not work when there was no cellphone coverage, and he promptly got lost.) Finally, the teen decided to raise money for Ronald McDonald House, a charity which offers free accommodation to families with children in hospital.

When his preparation was complete, Brando was taken by car to Cape Rēinga. This was more than merely a geographical location. It was the place of commitment to the mission; it was the time to walk the talk. His family bid him farewell, he wriggled into his huge pack, and he left the lighthouse. It was on 1 February 2013 when he set off into the rain.

On his first day, Brando clocked up 15 km wearing a pair of Vibram Fivefingers shoes. No doubt he was carrying too much on his back so the weight transferred to his legs, which seized with cramp. He set up a tent to bed down for the evening. With no sleeping mat beneath his body, curled up for warmth, the teen felt the cold creep into his bones — not a good start.

On his second day, Brando tested his underpowered air rifle. He managed to shoot a black-backed gull, roasting the bird over the flame of his portable gas stove. Though he tried to eat the half-cooked flesh, his meal was far from appetizing. (It should be noted that black-backed seagulls are not a protected species.)

Further south, along the vast expanse of Ninety Mile Beach, the teenager met many fishermen who offered him fresh fish to eat. In addition to these offerings, he killed and ate a possum. Brando was slowly becoming a junior version of Bear Grylls. About this time, he began to find his feet. He wrote: ‘I felt a connection; a drawing power to the land. For the first time in my life, I was consciously enjoying myself.’

Join the Discussion

Type out your comment here:

You must be logged in to post a comment.