In the ‘90s I bought a property in a place called Matakana. “Mata-where?” people used to ask, but 10 years on it seems as though everybody knows all about Matakana.

The same thing is happening with the rotator cuff tendons in the shoulder. When I first started work in 1989, injuries here were a relative rarity, whereas today it seems as though half my patients have rotator cuff problems, and every time I read the sports section of the paper, another high level sports person is getting a “shoulder reconstruction”. Statistics back up my observations: in 2000 ACC received claims for 23,383 new rotator cuff injuries with a total cost of around $36m. By 2007 there were over 40,711 new claims with a cost of $105m!

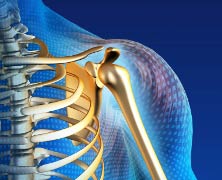

There appear to be a number of reasons for this epidemic, mainly attributable, I believe, to our modern lifestyle, but first a quick anatomy lesson. The shoulder joint is unique in that while it falls into the familiar and easily pictured “ball and socket” category, the socket is actually only 25% of the size of the ball. This structural geometry has been described as akin to “a golf ball sitting on a tee” and while it allows our shoulders their characteristic flexibility of movement, it also leaves them prone to instability. Compare, for example, the shoulder to a hip joint which is a much stronger joint but with considerably less flexibility – it takes a significant force such as a car accident to dislocate a hip whereas shoulders “pop out” regularly.

The shoulder gains most of its stability from a group of four relatively small muscles, the “rotator cuff”, which run from different points on your shoulder blade, through the shoulder joint and wrap over the top of the ball. These muscles work as a team, steering and stabilising the ball within the socket while the big muscles on the outside (the ones the blokes in the gyms love to build like the “pecs’ or deltoids) provide the force and power to move the arm. A good analogy is the rotors on a helicopter: the big one on top provides the power to lift and move the helicopter, the smaller one on the tail provides the control and stability. Power without control would be pointless.

Herein lies the first major problem: modern gym programmes. My apologies to the non-Darwinists amongst us, but the shoulder joint is unique in that it is designed for maximum mobility, and it is clearly perfect for climbing and swinging (think Tarzan). The healthiest (and best looking) shoulders I see are those of rock climbers: strong, muscular, and flexible yet stable from all the hanging and pulling up. Unlike hips and knees which require compressive forces to keep the bones and cartilage healthy, our shoulders were never designed for load bearing, in fact the only time in nature we would bench press a heavy weight, was when a tree fell on us. From then on we would avoid falling trees, not do three sets of 10 reps. Our gym programmes are full of press ups, bench press, shoulder press, military press, when our shoulders were designed to pull and extend. It always amazes me how many people I treat with shoulder problems who can do endless press-ups, or bench press twice their body weight, grinding their shoulders into submission, but can’t do a single pull up. Look at how effortlessly children can swing on the monkey bars – have you tried it lately?

Another problem with modern gym programmes is they focus on “extrinsic” muscles (I call them the beach muscles, the ones you can see), at the expense of the “intrinsic”, or protective, muscles (the rotator cuff). This is akin to having a Ferrari but equipped with cruddy brakes and shocks; looks good sitting still but would you want to drive it? Think back to the helicopter: what use is the powerful rotor providing lift without the smaller one providing stability? Isolating muscles when working out makes them big, it doesn’t make them useful. The next major problem is the lack of variety of movement our shoulders get. When we were cavemen, we used our shoulders for relatively short periods in a variety of ways; we climbed, ran, carried, dug, threw; now we polish the windows in our house on the weekend for 5 hours and wonder why our shoulders are sore, or sit at a keyboard for eight hours doing exactly the same thing over and over. They simply weren’t designed for this repetition. A classic example is swimming, which, while a great exercise for your heart and lungs, is tough on your shoulders (it even has a syndrome named after it- “swimmers’ shoulder”). I mean the only time a cave man swam was when he fell in the river and he swam like hell to the other side, got out and vowed to be more careful in future!

Don’t get me wrong, swimming is a great exercise, but variety is the key word. Churning endless, repetitive laps of freestyle might be good for your lungs but it wrecks your shoulders. Simply mix things up with some backstroke, some breast stroke, change pace with one lap hard, two laps easy. Just break the monotony.

The end result of modern exercise and modern lifestyle is the tightening up of the structures in the front of your shoulder generally seen as “round shouldered”.

With computers, cars, play stations, and the constant desire for bigger chests, the ball is gradually being dragged forward in the socket creating even greater pressure on the tendons lying within (a quick test to see if you are round shouldered is to stand facing a full length mirror- your thumbs should be pointing forwards and the palms of your hands parallel with your thighs- if you can see the back of your hands your shoulders have rolled forward). Teenagers have always been great at slouching (and I have no doubt at some point your mother told you to “stand up straight and pull your shoulders back”) but I am horrified at the neck and shoulder problems I used to associate with 55 year old accountants, now appearing in this age group. And the answer is relatively simple: variety in everything you do, whether it be swimming or computing, and change the way you exercise at the gym by working entire movements, not isolating muscles, and not grinding tendons. Oh, and hang from the occasional tree.

Article written by Robert D. Knight NZSP

Join the Discussion

Type out your comment here:

You must be logged in to post a comment.